The introduction of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) in the early 1980s revolutionized the treatment of patients with stones in the kidneys, ureter (the duct between the kidney and the bladder), pancreatic duct and bile ducts.

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy is a procedure to break up stones inside the urinary tract, bile ducts or pancreatic duct with a series of shock waves generated by a machine called a lithotripter.

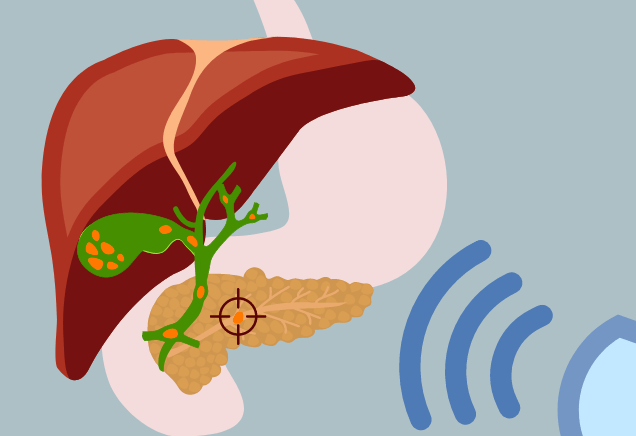

The shock waves enter the body and are targeted using an X-ray. The goal of the procedure is to break the stones into smaller pieces that can pass through the body or become easier to extract.

For stones in the kidneys and ureter, fragments will exit with urine. For stones in the bile ducts or pancreatic duct, large fragments may need to be removed by using an endoscope — a flexible tube inserted through the mouth.

ESWL works differently in various people, and is not always the best choice for someone who has a stone. The following are some of the factors that can affect the procedure’s success.

---Stone composition: Stones composed of cystine and certain types of calcium do not break up well with shock waves.

---Stone location: Stones in very narrow ducts may have trouble passing through or being extracted even after they are broken up.

---Stone size: Large stones may create big fragments that can be difficult to pass or extract.

---Preexisting conditions: Certain conditions, such as chronic infection, may make ESWL less effective.

Some ESWL techniques can make lithotripsy safer and more effective, such as adjusting the power and intervals of the shock waves.

Many people who once would have needed major surgery to remove kidney stones can be treated with ESWL without a single incision. ESWL is the main noninvasive treatment for kidney stones. It works well for people with smaller stones that can be easily seen with an X-ray.

ESWL is not recommended for people with chronic kidney infection, because some fragments may not pass and bacteria will not be completely eliminated from the kidney. It may also not work as well for those who have a blockage or scar tissue in the ureter, which may prevent stone fragments from passing.

Because ESWL is a noninvasive procedure, treatments are usually performed in an outpatient setting, meaning you can go home the same day. A mild anesthetic is usually used to numb the kidney area before the procedure.

Chronic pancreatitis leads to pancreatic duct stones for about 50% of patients. These stones can block the duct, causing pain and reduced flow of pancreatic enzymes needed for digestion. ESWL is often the first treatment used for large pancreatic duct stones. It is minimally invasive and often safer for removal of large stones than more traditional treatment: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

ERCP is usually used after ESWL to help extract the stone’s broken up fragments by using a flexible tube with a camera to reach the pancreas through the mouth. ERCP alone can cause pancreatic duct inflammation or injury, which ESWL helps avoid when performed before ERCP. When stones are broken into smaller fragments, they are easier to remove with the ERCP procedure and sometimes can even pass on their own.

General or spinal anesthesia (affecting the body below the waist) is usually used for people who receive ESWL with ERCP. Depending on the procedure’s results, you may be able to go home the same day or you may need to spend a night in the treatment center for observation.

Gallstones form in the gallbladder and can travel to the bile ducts, where they may get stuck. Gallstones are usually removed from the bile duct with the help of an endoscope. However, for some larger stones and those that are difficult to reach, ESWL might be used to break them up before extracting.

In the past, ESWL was used to break up stones in the gallbladder. However, ESWL is not effective in preventing the stones from coming back. Nowadays, minimally invasive gallbladder removal is a more common treatment for gallstones that cause symptoms.

The ESWL procedure takes about an hour, and sometimes longer depending on the size and number of the stones. During the procedure:

---You lie on a table in a specialized treatment room that has the shock wave machine and imaging equipment.

---After you receive anesthesia, the doctor will use a computerized X-ray machine, sometimes in combination with ultrasound, to pinpoint the stone’s location.

---The doctor will place you in the best position to aim the shock waves at the stone.

---A series of shock waves (several hundred to several thousand) is released at the stone. The doctor will adjust the power and the intervals of the shock waves as needed to break up the stone.

Pancreatic duct or bile duct stones broken up by ESWL may need to be extracted with an endoscope, which is done right after the ESWL procedure.

ESWL is generally considered safe. The shock waves target the stones with precision and typically do not damage surrounding organs and tissues.

However, some groups of people have higher risk of complications after ESWL. Your doctor may advise against ESWL if you:

---Are pregnant

---Have a pacemaker or another implanted device that can be disrupted by the shock waves

---Take blood thinners or have a bleeding disorder (you will need to stop taking aspirin or other blood thinners at least one week before ESWL)

---You need the stones removed urgently and completely, which ESWL cannot guarantee.

Original Link: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/kidney-stones/extracorporeal-shock-wave-lithotripsy-eswl